Art history is not only written in words, but in images too. Artists who enter the so-called canon are represented in art-historical image archives in a variety of ways and over a long period of time. The traces of the painter Lovis Corinth (1858–1925) in the Photothek of the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte (ZI) vividly illustrate the central role of reproductions in art-historical research and the perception of an artist.

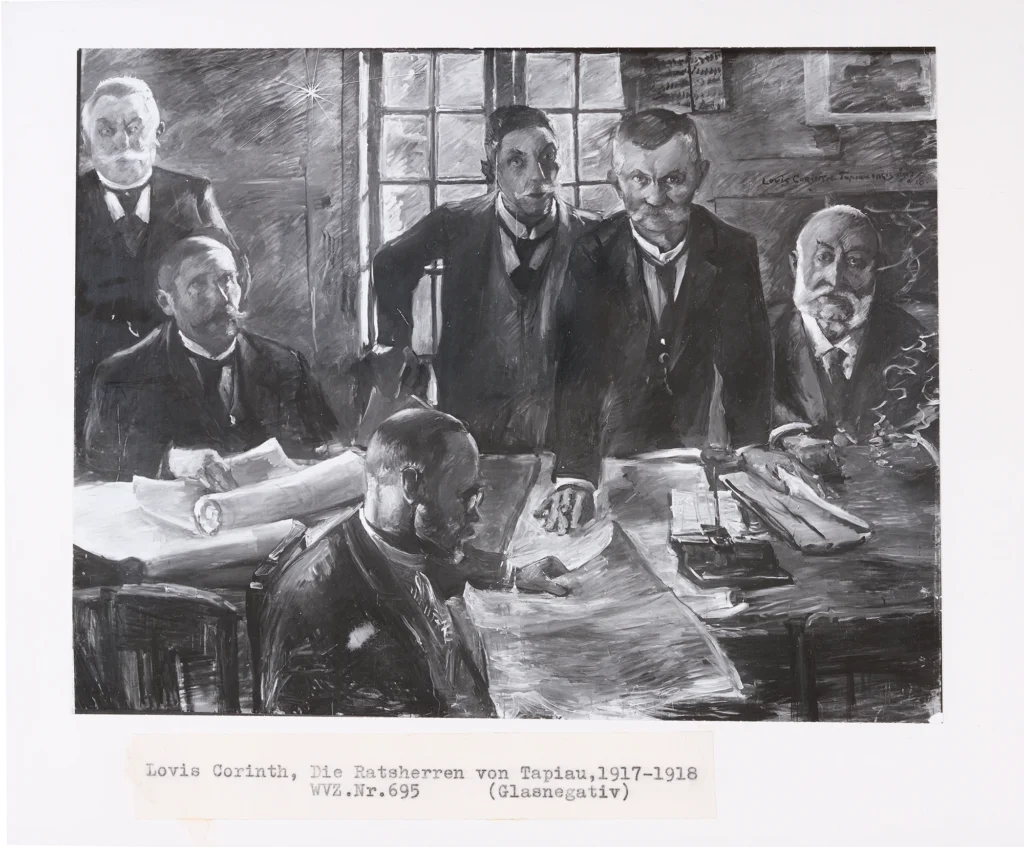

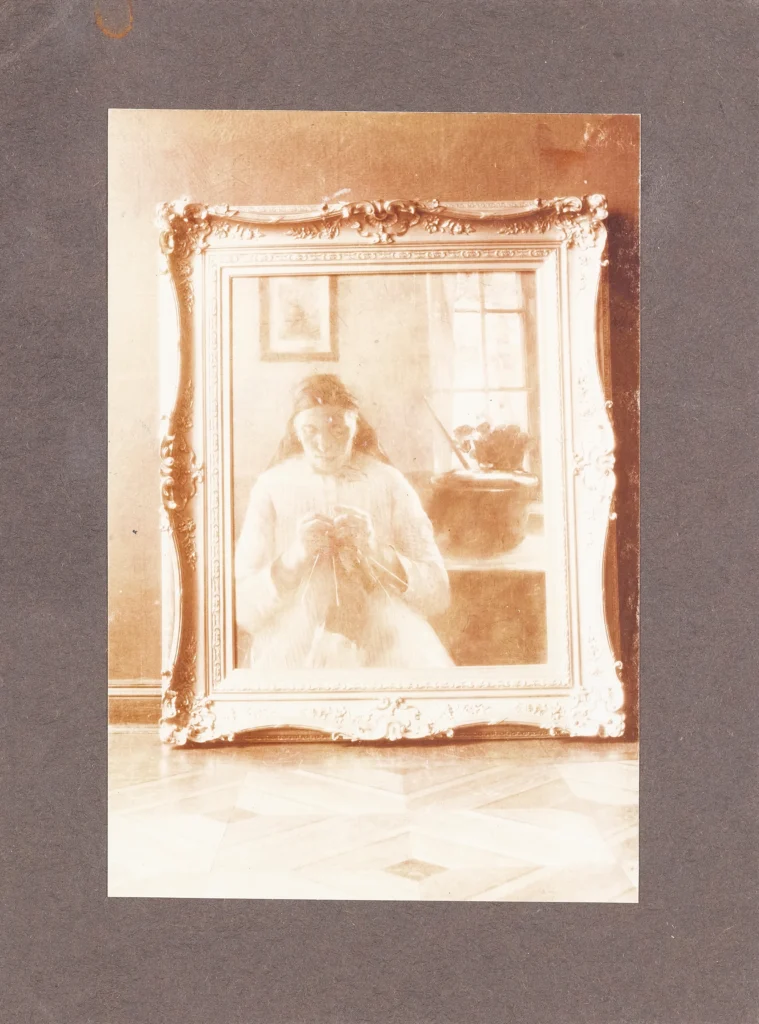

The Photothek preserves photographs documenting Corinth’s works and life across various holdings, including the Künstler-Abteilung (the collection of photographs sorted by artists), the Bruckmann Image Archive (containing material related to the Corinth catalogue raisonné) and the Schrey Collection. The range of media is extensive, with early albumen prints appearing alongside photogravures, glass negatives, silver gelatin prints, diapositives and ektachromes. This photographic ‚media mix‘, spanning more than a century, is a testament to the artist’s long-lasting presence, the multifaceted nature of his work, and the extent to which it has been reproduced, circulated and reinterpreted.

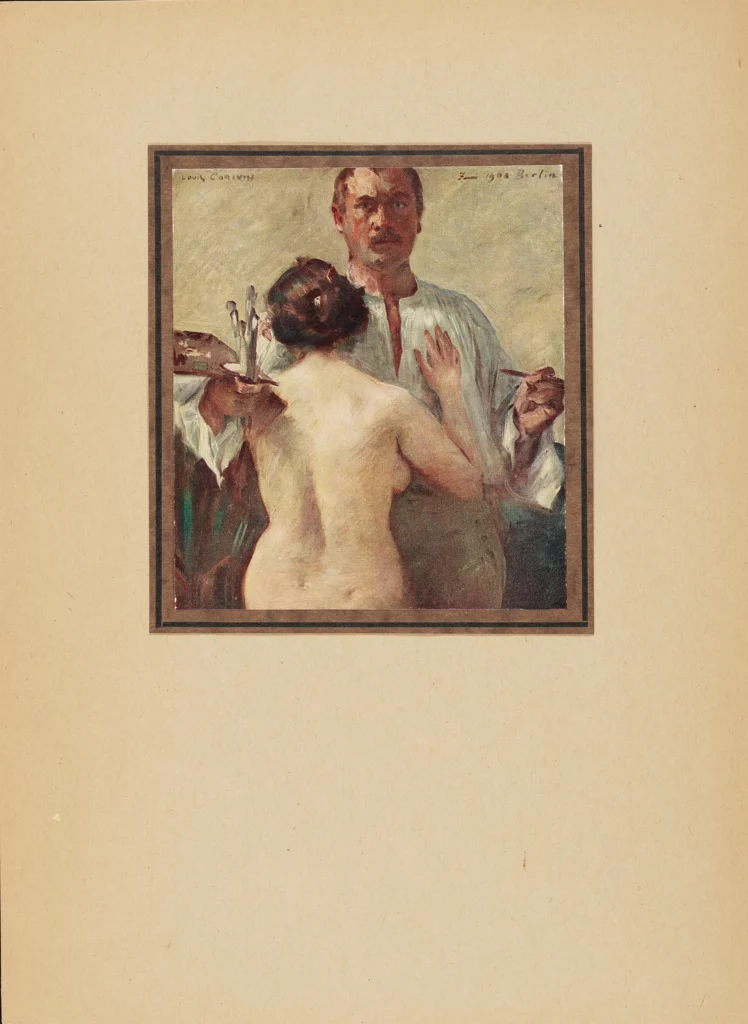

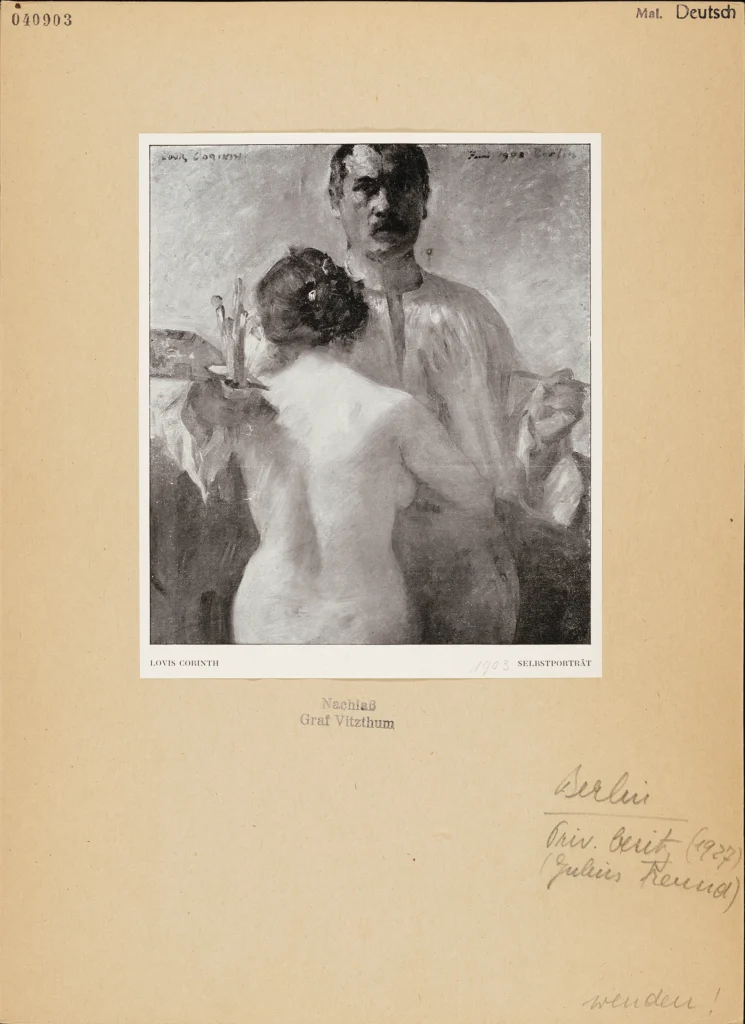

Although Corinth is well known for the vibrant colours in his paintings, his work was long studied almost exclusively through black-and-white reproductions unless the original was directly accessible. Art history was marked by a distinct ‚chromophobia‘: colour was considered distracting while form was considered paramount. According to an anecdote, Erwin Panofsky used to visit museums wearing sunglasses so that vivid colours would not divert his attention? (Monika Wagner: Kunstgeschichte in Schwarz-Weiß. Visuelle Argumente bei Panofsky und Warburg, in: Schwarz-Weiß als Evidenz, ed. by Monika Wagner and Helmut Lethen, Frankfurt am Main 2015, p. 139). A telling example from the ZI Photothek is a photograph of Corinth’s self-portrait with his wife, seen as a nude from the back (1903) mounted on cardboard. On the front, the work is reproduced in mediocre-quality black-and-white halftone, accompanied by the typical metadata. In the bottom right corner, there is a handwritten instruction to ‚turn over!‘. On the reverse, a colour reproduction of the painting has been mounted without comment, rendering it quite literally an image of second order.

Over the decades, collections of images emerged that were much more than just neutral documentation. These reproductions illustrate the diverse ways in which the objects were used and functioned: they were collected, labelled, categorised and sorted according to specific criteria to ensure clarity and accessibility. They served as research tools, for publication, as educational art materials, or as popular formats such as collector’s cards, as museums in miniature. In some cases, Corinth’s works were arranged classically by genre or motif, while in others they are organised by technique. In the Schrey Collection, for instance, Corinth is presented as a nineteenth-century artist. These systems of order reflect scholarly interests, as well as historically contingent valuations, hierarchies and art-historical perspectives. Every image mattered. Even damaged copies, such as those made from cracked glass negatives, as well as newspaper clippings and calendar pages, were preserved. The reproductions also provide information about the works‘ provenance and different appearances: whether they are framed or not, and whether they have been retouched, marked or cropped.

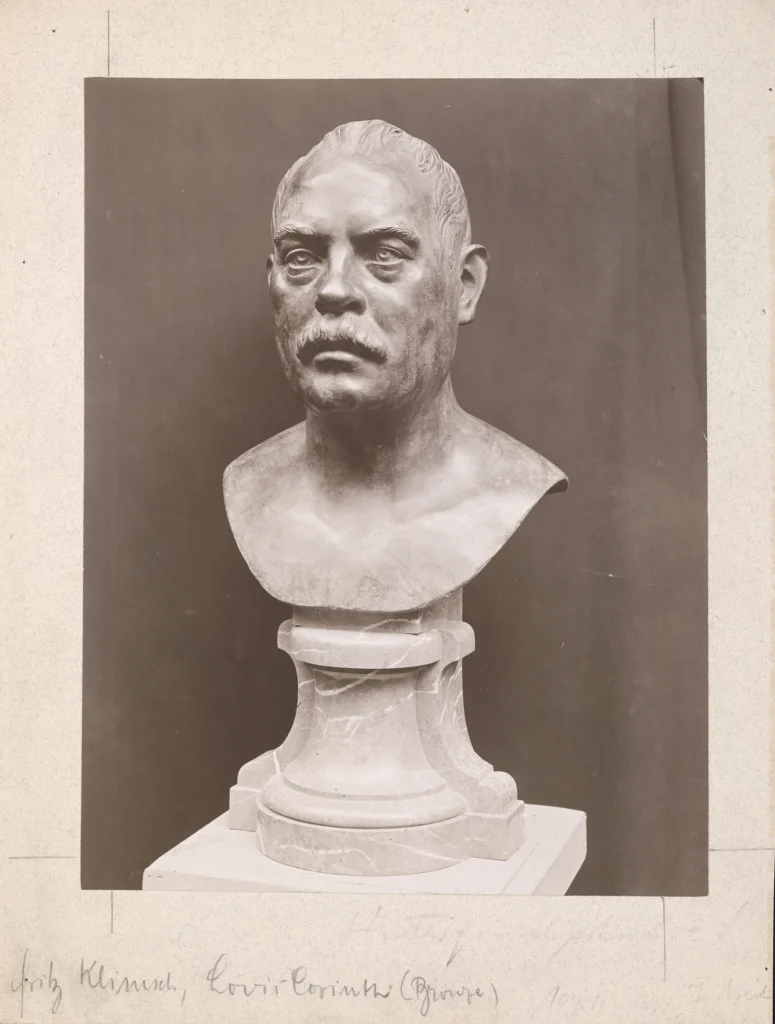

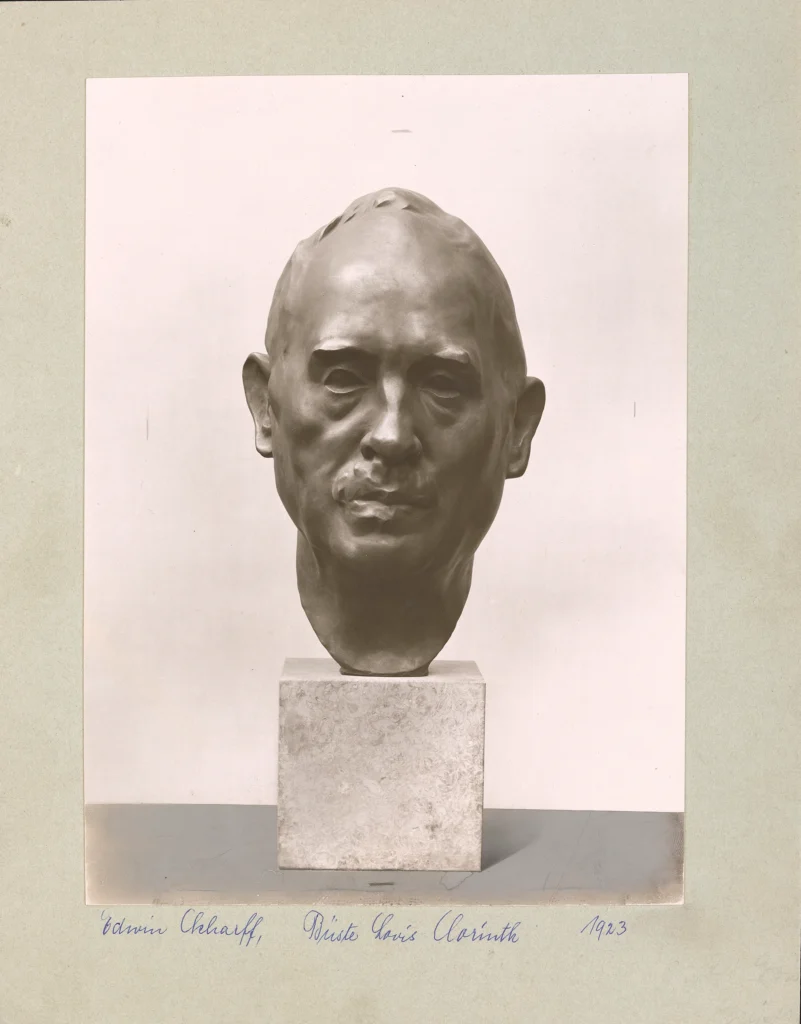

The image of an artist is never definitive. Rather, it emerges through the interplay of reception, personal relationships, and contemporary discourse. Family members, friends, fellow artists and the public all contribute different perspectives. The photographs preserved in the ZI Photothek likewise depict Lovis Corinth in various roles and modes of staging, such as a working artist in his studio where brush and sword converge symbolically, or as a subject portrayed by other artists. Of particular note are photographs of two portrait busts. Fritz Klimsch’s 1906 bronze bust presents Corinth as a powerful, energetic creator – an artist defined by his physical presence. In contrast, Edwin Scharff’s 1923 bust depicts Corinth as a contemplative, almost fragile intellectual: sensitive, restrained and refined. These contrasts highlight the fact that the image of the artist is always a reflection of its time and viewers.

Reproductions relating to Corinth’s life and work offer insight not only into his artistic production, but also into the broader history of art history itself, including its methods, media and image practices.

These and other photographs and reproduced images can be seen in the exhibition „Corinth werden! Der Künstler und die Kunstgeschichte“ at the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte (23.10.2025 –06.03.2026) in Munich.

DR. FRANZISKA LAMPE is deputy director of the photo library at the Zentralinstintit für Kunstgeschichte in Munich.

Further reading

- David Batchelor: Chromophobie – Angst vor der Farbe, Wien 2002.

- Monika Wagner: Kunstgeschichte in Schwarz-Weiß. Visuelle Argumente bei Panofsky und Warburg, in: Schwarz-Weiß als Evidenz, ed. by Monika Wagner and Helmut Lethen, Frankfurt am Main 2015, p. 126–144.

- Hana Gründler, Franziska Lampe and Katharine Stahlbuhk (Ed.): Phänomen ‚Farbe‘: Ästhetik – Epistemologie – Politik, kritische berichte, 1.2022

Schreibe einen Kommentar