Schlagwort: Ausstellung

-

Garden Futures and the Temporality of Critique

Weiterlesen: Garden Futures and the Temporality of CritiqueThe field of design has long evinced a self-reflexive relationship to the realm of non-human life conceptualized as “nature.” From the development of biomorphic form in response to the incipient industrialization of the crafts in the mid-nineteenth century to contemporary “eco-friendly” objects designed to sustain complex biotopes, designers have espoused a range of positions toward the transformation of nature by human agency.

-

Planetar oder doch global?

Weiterlesen: Planetar oder doch global?Eine Rezension von „Planetarische Bauern – Landwirtschaft, Kunst, Revolution“ im Kunstmuseum Moritzburg, Halle (Saale), 23. Mai bis 14. September 2025

-

The Missing Link

Weiterlesen: The Missing LinkLinn Burchert and Alexandra Masgras review Vernetzte Welten, on view at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg By the 1970s the term globalization gained currency in academic and corporate discourse as a means of describing the increasing interconnectedness of economies and cultures. Now an indubitable fact, globalization stirs attention across the political spectrum. While right-wing detractors are touting a protectionist vision of the (ethnic) nation-state, centrists retreat to shallow attempts to defend globalization as a peace-promoting, culture-enriching project. The contradictions brought about by globalization are also reflected in the legacy of the left. In the late 1990s and early 2000s left-wing groups…

-

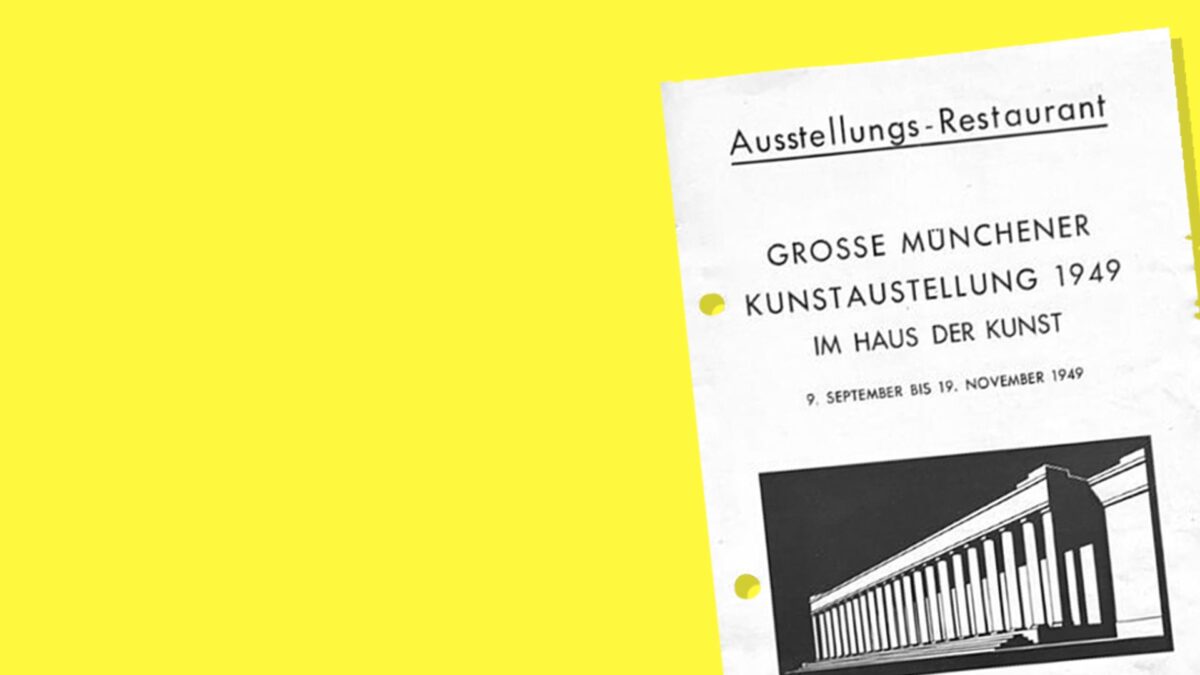

„Betrifft: ‚Große Kunstausstellung‘ im Frühjahr 1949“ – Julia Reich über neue Primärquellen zum Münchner Ausstellungsbetrieb der frühen Nachkriegszeit

Weiterlesen: „Betrifft: ‚Große Kunstausstellung‘ im Frühjahr 1949“ – Julia Reich über neue Primärquellen zum Münchner Ausstellungsbetrieb der frühen NachkriegszeitMünchen, Haus der Kunst, 8. September 1949: Der Maler Adolf Hartmann (1900–1972), Präsident der Ausstellungsleitung München e.V., eröffnet zusammen mit Kolleg*innen und Honoratioren die erste Große Münchner Kunstausstellung nach Kriegsende. Viele der Künstler*innen, die insgesamt mehr als 500 Werke zeigten, waren unter der nationalsozialistischen Diktatur zwölf Jahre lang als „entartet“ diffamiert worden, etwa Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Karl Caspar und dessen Frau Maria Caspar-Filser.

-

Mimesis or Ecology? Alexandra Masgras and Linn Burchert on Bauhaus Ecologies at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau

Weiterlesen: Mimesis or Ecology? Alexandra Masgras and Linn Burchert on Bauhaus Ecologies at the Bauhaus Museum DessauSince the Bauhaus centennial in 2019, academic and popular interest in what is often hailed as the world’s most famous design school has flourished. Arguably, the institution’s plight at the hands of right-wing municipal governments and later of the ruling Nazi party generated interest in several aspects of the Bauhäuslers’ practice identified as progressive. Their internationalism, the struggle against tradition and convention, as well as their gender-bending practices have all received renewed attention in recent years. The exhibition Bauhaus Ecologies held at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau (4 April – 2 November 2025) advances this line of inquiry by investigating the…

-

Travelling Back: Eine erneute Betrachtung der (Wissens-)Transfers zwischen München und Brasilien im 19. Jh.

Weiterlesen: Travelling Back: Eine erneute Betrachtung der (Wissens-)Transfers zwischen München und Brasilien im 19. Jh.Die Ausstellung Travelling Back, gezeigt zwischen Februar und April 2024 am Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in München, richtete einen kritischen Blick auf die Erzählungen und Sammlungen, welche die bayerischen Wissenschaftler Johann Baptist von Spix (1781–1826) und Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794–1868) im 19. Jahrhundert aus Brasilien mitbrachten.