The pandemic which is affecting the entire planet is changing our lifestyle and forces us to classify activities according to their level of ’necessity‘. Culture does not seem to be one of them: it is banned by fear.

The most beautiful public sites in the world – crowded before COVID-19 – have become deserted, almost ghostly places that instill anxiety. Museums, galleries, theatres, cultural institutions respond to this forced closure by challenging the ‚fear of culture‘ and promoting online events, virtual visits, weblogs, open access publications, and zoom webinars through social media.

This contingent reality makes us think of empty archaeological sites, and particularly of the villa of Emperor Hadrian (117-138) in Tivoli near Rome which after being abandoned, was damaged and neglected for many centuries. Since its rediscovery in the mid-15th century investigations have to confront and measure themselves against the fragmentary state of the imperial residence, stripped of its artistic and natural beauty, while trying to curb its deterioration. However, we know that the villa was originally characterized by a pulsating life, densely inhabited and impressively decorated.

In 1870, the Kingdom of Italy bought the lands of Hadrian’s Villa owned by the Braschi-Onesti family at a public auction, starting a program of redevelopment, restoration, and conservation, as well as excavation campaigns. Moreover, the villa was opened to the public. This goal was greatly achieved by improved means of transport and the development of tourism. Since 1999, the villa has been inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage List as “one of the most visited sites in Italy”.

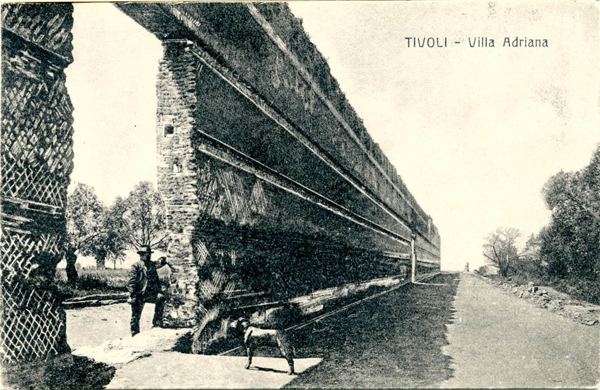

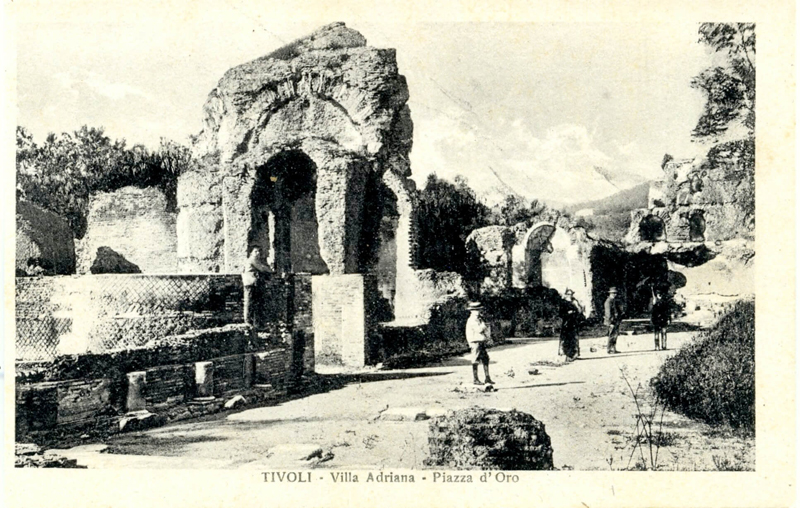

After a traditional reception of its buildings through predominantly graphic visual media, the advent of photography (mid-19th c.), had an impact on the perception and representation of Hadrian’s Villa, while recording and disseminating its image. Have a look at some historical images taken at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries presenting a partial repopulation and a kind of ‚appropriation‘ of the majestic ruins belonging to the largest villa of the Roman Empire.

They highlight the ratios of proportion between architecture and human beings.

With the highest respect for social distancing, solitary visitors at most in the company of their dog (Fig. 1) or small groups (Fig. 2 and 3) suggest a rapprochement and enjoyment of the ancient spaces, sometimes with a ‚historical‘ interpretation (Fig. 4).

The project Majestic Shadow of the Past – Tivoli and Hadrian’s villa in Photography between documentation and narrative (1870-1930) addresses the core question, if (and how) perception changed with the invention of new technology by both scholars and popular visitors. It aims to collect and evaluate miscellaneous photographic material related to Hadrian’s Villa, both as documentation and as narrative.

Dr. CRISTINA RUGGERO is currently Weinberg Fellow in Architectural History and Preservation at the Columbia University, NY.