Between 1484 and 1490, Michele di Bartolomeo alias “Tifi” Odasi, a man of letters who gravitated around the most distinguished humanistic circles of Padua, gave to the press a booklet that was destined to earn him a modest place in the history of Italian literature. Almost exclusively remembered today as one of the earliest examples of macaronic poetry, the humorous genre whose defining feature was an incongruous contamination of Latin language structures with vernacular words and inflections, his Macaronea nonetheless holds a certain interest for art historians. Along with the compositions by the Venetian Andrea Michieli, Odasi’s text marks the birth of a poetic tradition that would have enjoyed great popularity in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Italy – namely, the verse that ridiculed visual artists and their works. For among the many laughable characters who enliven the prank-based plot of the Macaronea, the most memorable is probably the one of the painter Canziano (text in Ivano Paccagnella, Le macaronee padovane. Tradizione e lingua, Padua 1979, pp. 120-21).

Leonardo da Vinci, Grotesque Head, ca. 1500, private collection (Foto: Wikimedia Commmons)

It is difficult to establish whether a historical artist might lie behind this literary figure, named after one of the most revered saints in renaissance Padua. However, this problem is of secondary importance if we focus on how Odasi lampoons Canziano as, first and foremost, the paradigm of the failed painter. In this perspective, it becomes evident how the author constructed the character by accumulating comic notations that were rooted in different poetic traditions. His textual portrait thus incorporates suggestions of ancient origins, mostly deriving from a set of mocking poems from the Planudean Anthology, along with motifs that enjoyed great popularity in the early centuries of Italian burlesque verse.

In the narrative of the Macaronea, Canziano owns a shabby workshop in the prestigious Paduan location of the Piazza dei Signori. We are told that his work as a varnisher of rudimentarily decorated cassoni and credenzas for rustic clients is rather successful, but that he cultivates the ambition to devote himself to the art of painting. Unfortunately, he has never really managed to learn the craft. The author thus underlines how Canziano’s attempts to paint something different from ornamental ceremonial rods always end up in litigations, because his dissatisfied clients systematically drag him into court to sue for refunds – and they have good reasons to do so. To begin, animal painting is not the artist’s forte: his painted roosters look like storks, his hunting dogs resemble free-swimming pikes, his goldfinches come off as chickens, and his chickens bear a conspicuous similarity to horses. We are also informed that his human figures are not really better off, because the men he depicts make one think of beheaded wooden mannequins.

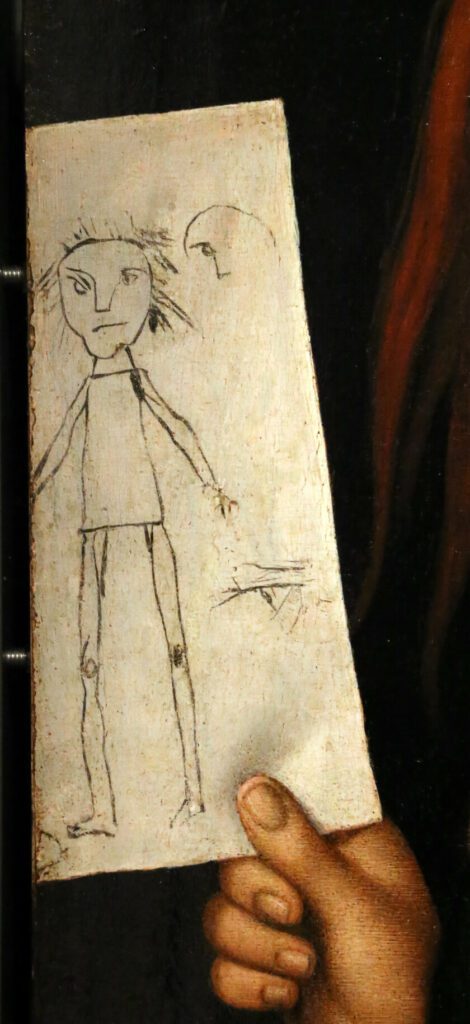

Giovan Francesco Caroto, Redheaded youth holding a drawing (detail), ca. 1523. Verona, Museo di Castelvecchio ( Foto: Wikimedia Commons).

Furthermore, apparently Canziano does not see any reason to shy away from standard contemporary subjects of secular and religious painting. As a result, the anatomy of the naked putti he depicts with much effort is of the least flattering kind, given how viewers are literally unable to discern face from ass in those figures. In his Madonna and Child pictures, on the other hand, beholders find it impossible to distinguish the former from the latter. Even so – the poet concludes – the painter has the gall of blaming his poorly manufactured brushes for his own mistakes, while also considering himself equal to one of the brothers Bellini.

Though amusing and worthy of consideration in its own terms, the criticism leveled at Canziano’s pictorial endeavors becomes particularly significant in a study of the shaping impact that the Antologia Planudea had on renaissance discourses on art. Among other things, the systemic mixture of classical and vernacular tropes that informs Odasi’s verse provides a good example of how art-critical motifs that were rooted in that collection were often appropriated by means of hybridization, of crossbreeding with elements from different literary backgrounds.

Dr. DILETTA GAMBERINI ist wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin am Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte mit dem Projekt “The Epigrammatic Gaze: The Italian Rediscovery of the Planudean Anthology and the Transformation of the Renaissance Culture of Viewing Art”