Surrounded by nature and beasts under her spell, Circe is still to this day one of the most famous sorceresses in classical literature. She is a key character for Book Ten of Homer’s Odyssey, and she reappears in Pseudo-Apollonius of Rhodes’ Argonautica, Ovid’s Metamorphoses, as well as in Virgil’s Aeneid. In each text, she uses her magic and her beauty to transform her victims into beasts, taking away their free will, their virility and their humanity. Odysseus avoids the same fate thanks to Mercury’s intervention, confronts Circe, and frees his men from their porcine appearance.

Roman authors significantly contributed to the development of a negative vision of Circe. Through their writings, the sorceress became a dangerous seductress driven by uncontrollable passion, a portrait that endures through Christian exegesis. In his influential commentary on Virgil’s Aeneid, Servius describes Circe as a “clarissima meretrix”, a famous prostitute and courtesan. Following him, Saint Augustine completed the diabolical transformation of the sorceress by calling her “the most famous of witches”. The Church Father strived to show that Circe’s transformations were nothing but deceptive illusions, associating the sorceress with demons throughout his discourse.

This negative image is perpetuated by Renaissance mythographers. During the period of the witch trials, Circe was often used in demonology treatises to prove the danger posed by witches and their ability to alter the bodies of their victims. Jean Bodin (1529/1530–1596), an author famous for his support of the persecution of witches, presents the Homeric account as irrefutable proof of these powers and supports his argument with two verses from the Odyssey describing Odysseus’ companions transformed.

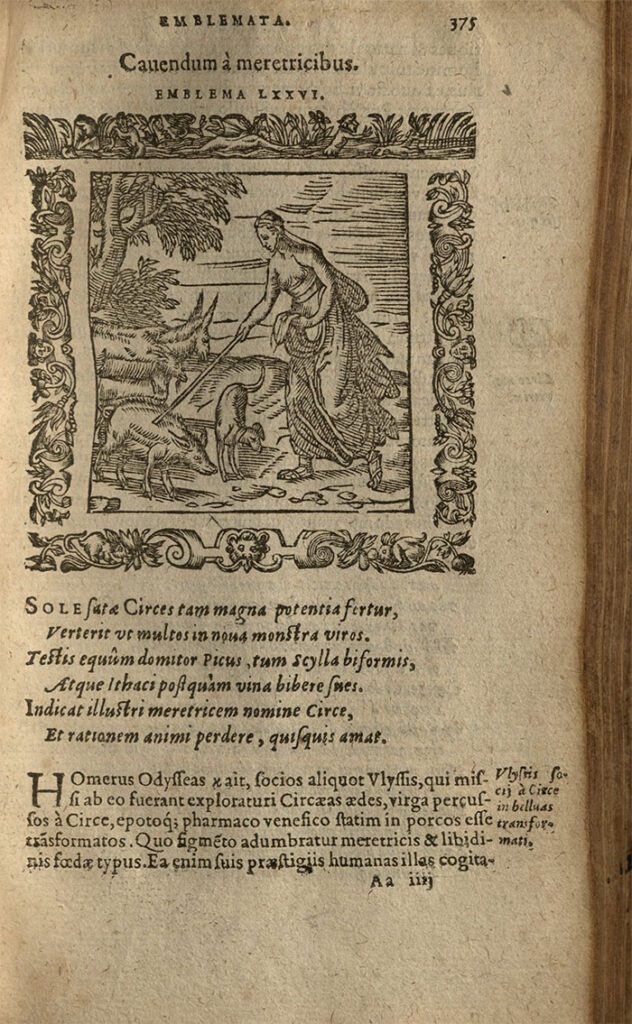

In Early modern art, Circe first appears in printmaking and illustrations of works by Boccaccio, Ovid, and Virgil. In Andrea Alciato’s Emblems, first published in Augsburg in 1531, Circe is already a depiction of reprehensible carnal pleasures. The 1546 Venetian edition includes a crowned figure approaching a group of swine (fig. 1). Next to the image are the Latin words “Cavendum a meretricibus” which can be translated as “Beware of prostitutes”. Here Circe is explicitly presented as the archetype of a dangerous prostitute, a woman who leads men astray from an exemplary life. She represents a subversive femininity capable of harming men.

In the last twenty years, scholars such as Charles Zika and Guy Tal have emphasized the lack of research conducted so far around the sorceress, who up until recently was seen as merely a minor character within the narrative of the Odyssey and barely examined within the framework of witchcraft iconography. In 16th and 17th century art, the figure of Circe is often highly eroticized, as in numerous examples by Bartholomeus Spranger (1546–1611) and Francesco Furini (c.1600–1646). Their lascivious bodies are dressed up and surrounded with motifs borrowed from learned magic and witchcraft iconography, which can be illustrated by the addition of grimoires to her repertoire of accessories.

In two oil paintings made around the middle of the 17th century (fig. 2), Gian Domenico Cerrini focused instead on the preparation of Circe’s poisoned wine. One of them (nowadays in the Musée Labenche, Brive-la-Gaillarde, France) was part of the Nazi spoliations that occurred during World War II and can be found in the inventory list of the Central Collecting Point of Munich (inv. n°13158). The enchantress is joined here by an unusually old handmaiden who unveils the breasts of her mistress while trying to peer into the mortar she is holding. The old woman is both trying to unravel the body of the enchantress and the secrets of her magic, hinting at early modern mythography where Circe is a personification of the transformative aspect of nature.

Finally, in a series of modelli (fig. 3) scattered around the world made as designs for several tapestries, Jacob Jordaens (1593–1678) furthers this discourse while focusing on the interaction between Circe and Odysseus, the latter fighting against her before becoming her lover and learning her secrets. Charming and seductive, Circe is a mistress of magic and a teacher for those who can resist her temptations.

PIERRE TCHEKHOFF, M.A., is this year’s Panofsky Fellow at the ZI. He is a PhD student in Art History from Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne University, writing his dissertation on the depiction of magic and enchantresses in early modern art under the supervision of Prof. Philippe Morel.

Selected Bibliography:

- Guy Tal: Art and witchcraft in Early Modern Italy, Amsterdam, 2023.

- Bertina Suida Manning: “The Transformation of Circe: The Significance of the Sorceress as Subject in 17th Century Genoese Painting” in Scritti di storia dell’arte in onore di Federico Zeri, Milan, 1984, 689-708.

- Judith Yarnall: Transformations of Circe: the history of an enchantress, Urbana, 1994

- Charles Zika: “Images of Circe and Discourses of Witchcraft, 1480 – 1580” in: Zeitenblicke 1 (2002).