An alpha automobile city, saturated with parked cars, Munich has been transformed during the pandemic, at least in part, by the sudden appearance of pop-up al fresco dining shacks constructed in the road and displacing at least some of those seemingly permanently parked cars. For cyclists, it has been a joy to behold and runs no risk of a suddenly opening door when passing by. Yet how did this phenomenon manage to appear ‘overnight’ given that gastronomy is one of the most regulated of industries and Munich one of the most regulated cities?

Previous to the pandemic, outside dining in an urban context was mostly confined to the pavement and regulation was principally to do with how much space could be occupied by tables and chairs in order to leave enough space for pedestrians. Operating hours that respected neighbours were also regulated as it was and is for bars. The ‘leap’ into the street itself meant less space for parked cars, always at a premium well before the pandemic, yet hardly anyone seems to have protested or minded much. Munich council embraced the move, not entirely altruistically, because they charge a fee for road occupancy by al fresco dining shacks where previously these spaces were occupied by residents’ cars with parking permits.

Restaurant owners need to make an application to the Kreisverwaltungsreferat (Department of Public Order) in Munich and in many cases, requests in 2020 were turned down, whereas many more applications were accepted in 2021, perhaps because of the ongoing nature of the pandemic. The main criterion is that these shacks must respect the 1.5 metre distance between tables and that they must not be enclosed structures. This is in stark contrast to the very permanent installations that operate on the via Vittorio Veneto in Rome throughout the year. Munich council has also given some slack to hard-hit restaurateurs in that the applications approved for 2021 will only led to the payment of an annual fee in 2022. From those interviewed, they are certain they will earn more from the extra outdoor seating than what they pay in ground rent. In addition, but perhaps not for this reason, the council will earn more money from these ground rents because, in the past, these spaces have been occupied by residents’ cars. In any case, for the wider streets, such as Heimeranstraße in Munich’s Westend, there are no fines for parking alongside the dining shacks in the road. This does not hold true, for example, for Schwanthalerstraße where, being so narrow, the occupation of the road parking areas literally deprives residents in this area of a certain number of legitimate spaces and it may be the case that there have been local protests by automobile drivers there.

Normally with al fresco dining, two metres of pavement must be left free for pedestrians and the cycle lane and this remains the case. For the most part, the new dining shacks, so often decorated with flowers in pots, can be considered a significant improvement to the streets of Munich. This is not that type of hideous ‘arredo urbano’ that leaves one gasping for comprehension and serves no purpose. Rather, the ‘beauty’ of these al fresco dining shacks is that they are perennial, will close down in the winter and will, like flowers and plants, bounce back into action in the spring. The joy of seeing and sitting in these in this past year has been one of the few positive things to have come out of the pandemic. Less streets saturated with permanently parked cars has been another. And this manoeuvre should not be entirely surprising: after all Munich is home to one of the oldest phenomena of perennial al fresco dining and drinking shacks in the world: Oktoberfest.

Prof. Dr. ANDREW HOPKINS FSA holds the Chair of Architectural History in the Dipartimento di Scienze Umane of the Università degli studi dell’Aquila in Italy. His main interests are the architecture, urbanism and landscapes of cities and he published on the seventeenth-century cities of Europe in La città del Seicento (Rome: Laterza, 2014).

Christine Tauber über eine vergessene Pilgerstätte für Royalisten

PARISER TROUVAILLE NR. 3 Selbst ausgewiesene Paris-Kenner kann man in Erstaunen versetzen, wenn man sie…

Auf der Suche nach der Mitte: Oliver Sukrow über das „Haus der Kultur“ in Gera

Als bauliches Ergebnis der langwierigen Suche nach einem definierenden Zentrum prägt der Komplex des „Haus…

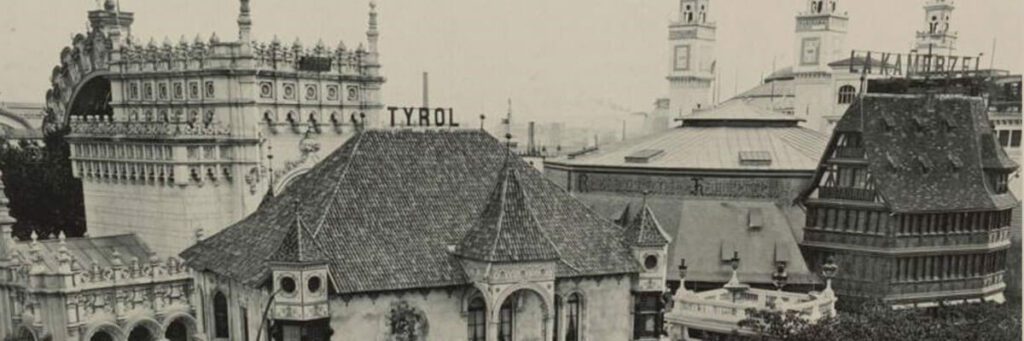

Krista Profanter über das „Château Tyrolien“ auf der Pariser Weltausstellung 1900

Tirol war auf der Weltausstellung in Paris 1900 mit einem eigenen Pavillon vertreten (Abb. 1)….

Christine Tauber zu Napoleon III. als Pionier des sozialen Wohnungsbaus

PARISER TROUVAILLE NR. 1 Im Dezember 1848, nach der dritten Pariser Revolution, wird Louis Napoléon,…