Autor: ZI

-

Cosima Dollansky über eingekapselte Biografien in Kunsthandelsquellen

Weiterlesen: Cosima Dollansky über eingekapselte Biografien in KunsthandelsquellenAnnotierte Auktionskataloge sind vor allem für die Provenienzforschung eine wichtige, manchmal sogar die einzige Ressource, um einen früheren Besitzer oder eine frühere Besitzerin zu ermitteln. Hinter einigen Namen verbergen sich Biografien mit tragischem Schicksal, die erst in der Zusammenschau mit weiteren (Kunsthandels-)Quellen enthüllt werden.

-

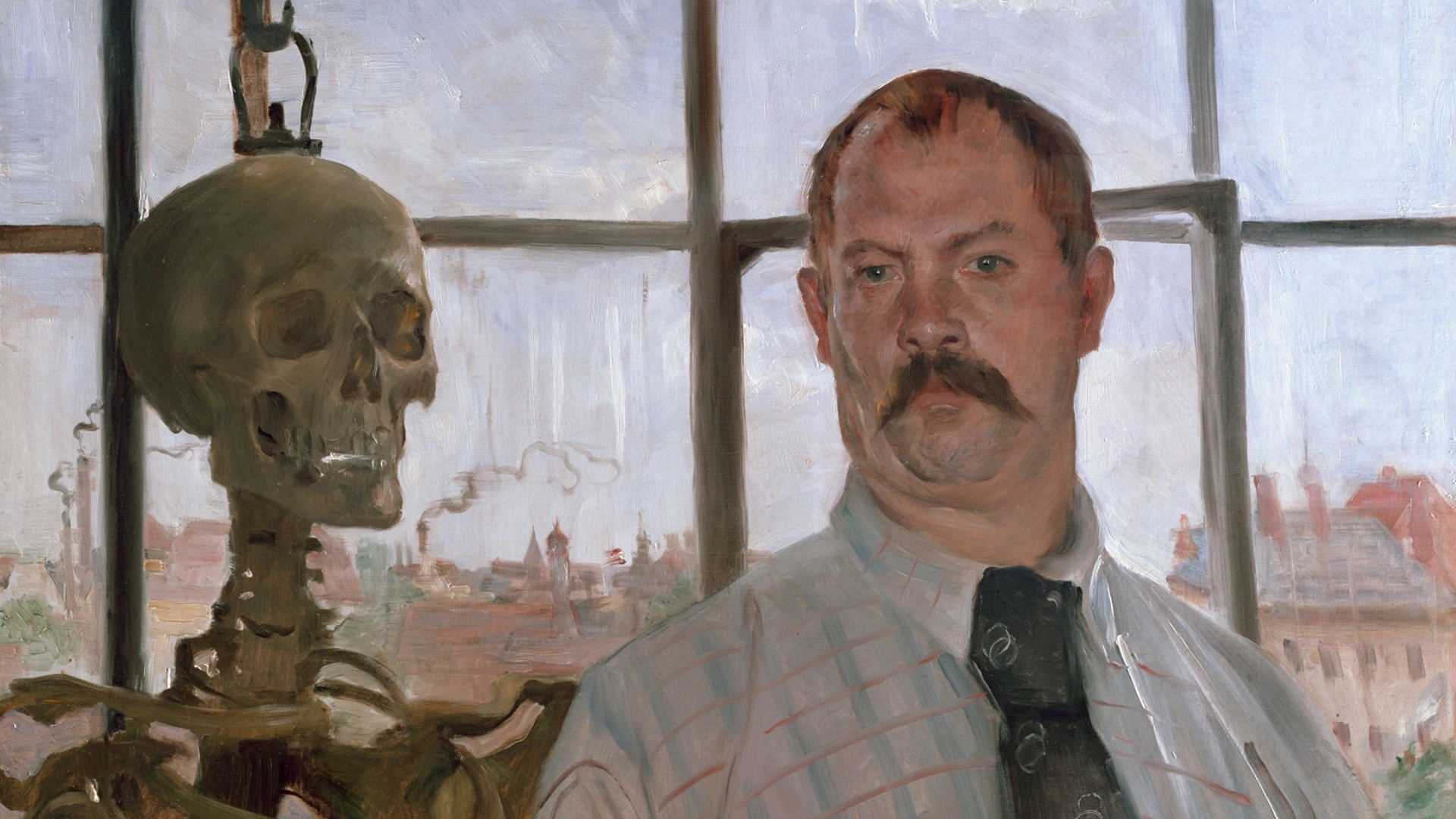

Dominik Brabant zu Lovis Corinth x 3

Weiterlesen: Dominik Brabant zu Lovis Corinth x 3„Corinth without a mask”?: Horst Uhr: Lovis Corinth, Berkeley u.a. 1990 | Dreimal „Lovis Corinth“. Mit der Wahl lediglich von Vor- und Nachname für ihre jeweiligen Buchtitel erheben die drei Autoren Georg Biermann (>>), Hans von der Osten (>>) und Horst Uhr den Anspruch, jeweils ein umfassendes Bild der Biographie des Künstler und – metonymisch…

-

Dominik Brabant zu Lovis Corinth x 3

Weiterlesen: Dominik Brabant zu Lovis Corinth x 3Im „quellend ‚Feuchten‘ der Malerei“: Gert von der Osten: Lovis Corinth, München 1955 | Der Kunstschriftsteller Georg Biermann, dessen Corinth-Monographie in der vorangegangenen Ausgabe von ZI Spotlight im Zentrum stand (>>), präsentierte seinem Lesepublikum noch selbstbewusst das Narrativ des Künstlers als durchsetzungsfähiger Kämpfer für die eigenen künstlerischen Überzeugungen. In seiner gut vierzig Jahre später veröffentlichten…

-

Dominik Brabant zu Lovis Corinth x 3

Weiterlesen: Dominik Brabant zu Lovis Corinth x 3„Feder und Pinsel sind seine Waffen geworden“: Georg Biermann: Lovis Corinth, Bielefeld/Leipzig 1913 | Drei Monographien gleichen Titels, verfasst von drei unterschiedlichen Autoren, jeweils im Abstand von etwa 40 Jahren.

-

Sibylle Weber am Bach über Reproduktionen, die Kunstgeschichte schrieben

Weiterlesen: Sibylle Weber am Bach über Reproduktionen, die Kunstgeschichte schriebenKunsthistorische Kennerschaft stützte sich bis weit in das 20. Jahrhundert zu großen Teilen auf Schwarz-Weiß-Aufnahmen. Damals maßgebliche Methoden der Kunstgeschichte wie die Stilgeschichte, die Ikonographie und die Ikonologie wurden anhand von Schwarz-Weiß-Reproduktionen entwickelt und sukzessive verfeinert. In Forschung und Lehre wie im Kunsthandel, im privaten Arbeitszimmer und in Museen boten sie die entscheidende Grundlage für…

-

Garden Futures and the Temporality of Critique

Weiterlesen: Garden Futures and the Temporality of CritiqueThe field of design has long evinced a self-reflexive relationship to the realm of non-human life conceptualized as “nature.” From the development of biomorphic form in response to the incipient industrialization of the crafts in the mid-nineteenth century to contemporary “eco-friendly” objects designed to sustain complex biotopes, designers have espoused a range of positions toward…